|

The Kartvelologist The Kartvelologist” is a bilingual (Georgian and English) peer-reviewed, academic journal, covering all spheres of Kartvelological scholarship. Along with introducing scholarly novelties in Georgian Studies, it aims at popularization of essays of Georgian researchers on the international level and diffusion of foreign Kartvelological scholarship in Georgian scholarly circles. “The Kartvelologist” issues both in printed and electronic form. In 1993-2009 it came out only in printed form (#1-15). The publisher is the “Centre for Kartvelian Studies” (TSU), financially supported by the “Fund of the Kartvelological School”. In 2011-2013 the journal is financed by Shota Rustaveli National Science Foundation. |

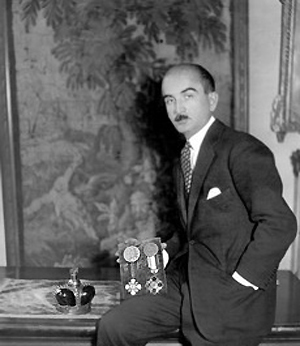

The Unknown George (Giorgi) Papashvily

George (Giorgi) Papashvily is entered in such serious publications as Who’s Who in American Arts, as well as Who’s Who in American Literature of the 20th century. In Soviet space Papashvily belonged to “banned culture.” In parallel to this there also was the phrase: “unknown culture”. Although rarely, yet opportunities arose of familiarizing oneself with this culture. keywords:Giorgi Papashvily, Hellen Waite Papashvily, Georgian emigrant Category: CHRONICLE OF EVENTS Authors: Rusudan Nishnianidze Katharine Vivian (1217-2010)

Katharine Vivian was born in October 1917. In 1939 she married Anthony Ashton, who later became a well-known statesman. Katharine graduated from Sorbonne University, majoring in French civilization. Initially, she took up journalism. During World War Two she served at the Belgian Embassy in London. After the War she continued her studies in French and English literature and philosophy. keywords:Katharine Vivian, “The Man in the Panther Skin”, “The Book of Wisdom and Lies”, the “Georgian Chronicle”. Category: KARTVELOLOGISTS Authors: Marika Odzeli The Oldest Georgian Hymn in “The Nine Martyred Children of Kola”

As the author of “The Nine Martyred Children of Kola” notes, before baptism the children were not allowed to enter the church. Therefore the church in the village of Kola had the form of a cell and it didn’t have a porch, the place for staying of catechumens. This must have taken place in the 2nd -3rd centuries.

keywords:hymn, “The Nine Martyred Children of Kola”, hagiography Category: SCHOLARLY STUDIES Authors: Ia Grigalashvili Kartvelian Folktales in German

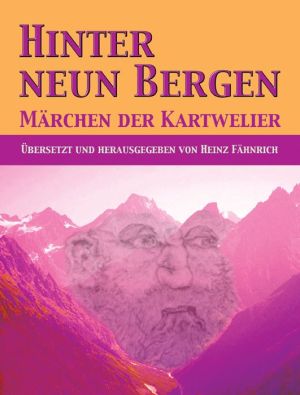

keywords:Heinz Fähnrich, folktales, Georgia, Caucasus Category: CHRONICLE OF EVENTS Authors: Elene Gogiashvili

THE MAN IN THE PANTHER SKIN - Prologue

The traditional section of our journal “Georgian Literature in English Translations” might seem peculiar in the present issue. It features the Prologue of MPS in all English language translations to date. These are by Marjory Wardrop, done at the turn of the 19th-20th c. (the text is taken from the 1912 London edition (The Royal Asiatic Society); Venera Urushadze (first issue 1968; the text is printed according to the author’s revised edition (Tbilisi: Sabchota Sakartvelo, 1986); Katharine Vivian (London: The Folio Society, 1977); Robert Stevenson (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1977). The Georgian text is printed according to the edition of the Commission for the Establishment of the Academic Text of MPS (Tbilisi: Metsniereba, 1988). What is the publication of the Georgian text with the four parallel translations due to? MPS is the peak of Medieval Georgian literary and socio-political thought. The poem clearly echoes the progress of European Christian thought from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance. This process of social thinking is reflected in MPS not only in its artistic system but in its theoretical-discursive form as well – mainly in the Prologue. This fact imparts special significance to this section of the poem. Though Rustvali’s language of the Prologue is plain Georgian; with its theological-philosophical connotations it differs essentially from modern Georgian philosophical definitions. The Prologue conceptions of MPS on the Creation by the Supreme Being, definition of spirit and perspective of motion, man’s moral and physical virtues, the essence of poetry and love with the forms of its expression; as well as on the twelfth-century Georgian royal court and the poet’s relation to, the provenance of the plot of the poem and the principal manifestation of the emotional activity of the characters – are formulated by the poet using the philosophical-theological and scholastic-mystic thought definitions of his time. The conceptions found in the Prologue of MPS rest firmly on biblical – largely New Testament – theology, on the one hand, and Greek philosophy of the Classical and Hellenistic periods, namely Plato, Aristotle and Dionysius the Areopagite, on the other. Gaining insight into the essence of these unique conceptions of medieval philosophical-theological thought forms an actual question of present-day Rustaveli studies. The interest taken in this problem, and in general in MPS as a whole, by European intellectual circles, in particular medieval and Renaisance researchers, clearly taking shape in recent decades, calls for the presentation of the text of MPS, and primarily its theoretical conceptions for the non-Georgian readers. None of the translations known to date can shoulder this mission. This is the primary reason for our decision to supply the English-language reader with all the translations of the Prologue. This attempt has naturally another no less important purpose: parallel observation of the four translations will clearly reveal the poetic merits of each of them. The desire to render Rustaveli in another language comes across numerous difficulties. Take, for that matter the title of the poem. In Wardrop’s translation it is The Man in the Panther’s Skin, in Urushadze’s The Knight in the Panther’s Skin, in Vivian’s The Knight in Panther Skin, in Stevenson’s The Lord in the Panther-skin. Of the nuances that differentiate these titles, I shall draw attention to only one Man, Knight and Lord are accepted interpretations for a natural perception of the Georgian –osan suffix (Vepkhistqaosani) in English. All these titles are more or less contradictory. An exact, though literarily hardly acceptable, rendering would be “one who wears a panther’s skin” or more precisely “wearer of a panther’s skin”. My touching on the rendering in English of the title of Rustaveli’s poem is due to the present subsection bearing the title The Man in the Panther Skin, which seems to me a modern contamination of the versions of English translations of the poem.

The Editor keywords:Rustaveli, The Man in the Panther Skin Category: GEORGIAN LITERATURE IN ENGLISH TRANSLATION Authors: SHOTA RUSTAVELI |

Categories Journal Archive |

The paper deals with the Georgian born well-known American sculptor and writer George (Giorgi) Papashvily. His works are preserved in state museums and private collections. His book “Anything Can Happen”, written in co-authorship with his wife Hellen Waite Papashvily, was acknowledged a best-seller and called an unprecedented event: George Papashviliy’s works constitute a landmark in the history of Georgian-American culture.

The paper deals with the Georgian born well-known American sculptor and writer George (Giorgi) Papashvily. His works are preserved in state museums and private collections. His book “Anything Can Happen”, written in co-authorship with his wife Hellen Waite Papashvily, was acknowledged a best-seller and called an unprecedented event: George Papashviliy’s works constitute a landmark in the history of Georgian-American culture. The name of the well-known British Kartvelologist of the twentieth century Katharine Vivian today belongs to history. Beginning with the 1970s her contacts with Georgians were very close, enjoying high respect. She took up with honour the work of her predecessor Marjory Wardrop, shouldering the translation and study of landmarks of Georgian literature into English. Her activity contributed much to the process of integrating Georgian culture into European space.

The name of the well-known British Kartvelologist of the twentieth century Katharine Vivian today belongs to history. Beginning with the 1970s her contacts with Georgians were very close, enjoying high respect. She took up with honour the work of her predecessor Marjory Wardrop, shouldering the translation and study of landmarks of Georgian literature into English. Her activity contributed much to the process of integrating Georgian culture into European space. The determination of the date of compilation of “The Nine Martyred Children of Kola” always gave birth to differences of opinions in Georgian scholarship. In the recent period the opinion that “The Nine Martyred Children of Kola” was written in the 2nd -3rd centuries is becoming popular. In support of this opinion I argue that dressing the children in white robes, their stepping down into the stream, singing of an improvised hymn by the priest might be characteristic of the church service practice of the 2nd-3rd centuries. It is difficult to define whether the hymn was translated from any language, or the author improvised it? It is clear that the translator must have based himself on the nature of the Georgian language, versification of that time, or hymn or form of a pagan hymn. The fact is that the hymn is of rhythmic character. I divided it into lines.

The determination of the date of compilation of “The Nine Martyred Children of Kola” always gave birth to differences of opinions in Georgian scholarship. In the recent period the opinion that “The Nine Martyred Children of Kola” was written in the 2nd -3rd centuries is becoming popular. In support of this opinion I argue that dressing the children in white robes, their stepping down into the stream, singing of an improvised hymn by the priest might be characteristic of the church service practice of the 2nd-3rd centuries. It is difficult to define whether the hymn was translated from any language, or the author improvised it? It is clear that the translator must have based himself on the nature of the Georgian language, versification of that time, or hymn or form of a pagan hymn. The fact is that the hymn is of rhythmic character. I divided it into lines.  The well-known German Kartvelologist Heinz Fähnrich has regularly edited Georgian folklore in the form of numerous books: Epic of Amirani (1978), Georgian folktales (1963, 1980, 1995), Georgian tales (1984), Georgian tales and legends (1998), Svan folktales (1992), Laz folktales (1995), Mingrelian tales (1997), lexicon of Georgian Mythology (1999) etc. “Behind Nine Mountains. Folktales of Georgians” constitutes one more corpus of Georgian folktales in German [1]. More than 170 Georgian folktales from Georgian, Mingrelian, Laz and Svan folklore are collected in the book: magic, novelistic and animal tales with epilogue, lexicon and bibliography. Folklore and literary sources are given in the appendix as well (pp. 636-645). Specific Georgian words which are used in the German text without translation are also explained at the end of the book, for example, the names of musical instruments, money, traditional food, ethnographic things, nicknames, toponymy etc.

The well-known German Kartvelologist Heinz Fähnrich has regularly edited Georgian folklore in the form of numerous books: Epic of Amirani (1978), Georgian folktales (1963, 1980, 1995), Georgian tales (1984), Georgian tales and legends (1998), Svan folktales (1992), Laz folktales (1995), Mingrelian tales (1997), lexicon of Georgian Mythology (1999) etc. “Behind Nine Mountains. Folktales of Georgians” constitutes one more corpus of Georgian folktales in German [1]. More than 170 Georgian folktales from Georgian, Mingrelian, Laz and Svan folklore are collected in the book: magic, novelistic and animal tales with epilogue, lexicon and bibliography. Folklore and literary sources are given in the appendix as well (pp. 636-645). Specific Georgian words which are used in the German text without translation are also explained at the end of the book, for example, the names of musical instruments, money, traditional food, ethnographic things, nicknames, toponymy etc.