|

The Kartvelologist

The Kartvelologist” is a bilingual (Georgian and English) peer-reviewed, academic journal, covering all spheres

of Kartvelological scholarship. Along with introducing scholarly novelties in Georgian Studies, it

aims at popularization of essays of Georgian researchers on the international level and diffusion of

foreign Kartvelological scholarship in Georgian scholarly circles.

“The Kartvelologist” issues both in printed and electronic form. In 1993-2009 it came out only

in printed form (#1-15). The publisher is the “Centre for Kartvelian Studies” (TSU), financially

supported by the “Fund of the Kartvelological School”. In 2011-2013 the journal is financed by

Shota Rustaveli National Science Foundation.

|

Ia Grigalashvili

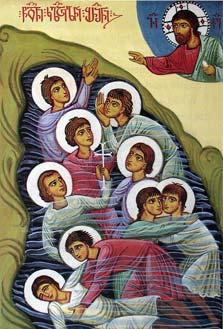

The Oldest Georgian Hymn in “The Nine Martyred Children of Kola”

In this country church service - derived from Jerusalem church service practice - was approved in an early period of spreading of Christianity. In “The Nine Martyred Children of Kola” by an unknown author the character of the service of the apostolic church of the 2nd-3rd centuries is clearly defined. The oldest rule of baptism and the oldest Georgian hymn are reflected in “The Martyrdom”. In this country church service - derived from Jerusalem church service practice - was approved in an early period of spreading of Christianity. In “The Nine Martyred Children of Kola” by an unknown author the character of the service of the apostolic church of the 2nd-3rd centuries is clearly defined. The oldest rule of baptism and the oldest Georgian hymn are reflected in “The Martyrdom”.

It’s known that the Saint Apostles defined the rule of baptism based on the teaching of Jesus and handed it down to their successors. Baptism of the St Apostles’ epoch (in the 2nd-3rd centuries) differed with its simplicity and consisted in: being instructed in the faith of Jesus Christ, rejection of sins, open confession of Christ’s faith, dipping in the water and saying the words: “In the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Ghost!”

At the end of the 2nd century and at the beginning of the 3rd century preparation for baptism lasted for a few days or years. In accepting a new person, they were very cautious not to receive the weak in the faith, because they could disown Christ under persecution and denounce Christians before the pagans. In the 3rd century baptism was preceded by swearing an oath, rejecting Satan, shared views with Christ, after which they anointed the whole body. Before dipping the catechumen the water was consecrated. After baptism the newly-baptized was dressed in a white robe. They crowned them (in the West) and gave a cross. Fulfillment of the rule of baptism that began in the 2nd century significantly strengthened in the 3rd century, continuing in the 4th and 5th centuries, though not in the same way as it was before. That time the liturgical side attained the fullest development. Many of the prayers which exist now in the liturgy of catechumen by consecrating the water and baptism were compiled in the 4th-8th centuries [15, p. 18-19].

As the author of “The Nine Martyred Children of Kola” tells us that the priest baptized the children who wanted to be baptized as Christians at night in winter, “for by day he would not have dared to baptize them for fear of the pagans. Furthermore our Lord Jesus Christ was also baptized by night by John in the river Jordan.

At this season the water gave out an icy sharpness, but when the children stepped down into the stream and the priest baptized them in the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Ghost, and pronounced the following sacramental words: “The Holy Ghost descended as a dove upon the Jordan when Christ was baptized. The angels stood by singing hymns-Alleluia, Alleluia”-then the water gave out great warmth, just like a bath. And by the will of God, angels brought down white robes from heaven and dressed the newly baptized children in them, invisibly to men.” (The translation of the passage quoted from D. M. Lang, Lives and Legends of the Georgian Saints, London, 1956, pp.41-42).

As the author remarks, the priest baptized the children at night in winter because he did not dare to baptise them by day. Therefore, by that time when the described story happens in the “Martyrdom” Christianity is not acknowledged as official, state religion. Accordingly, the priest is unprotected in the state of the pagans. However, the author of the “Martyrdom” tries to explain such action of the priest and notes that Christ was also baptized in the river Jordan at night. According to Pavle Ingoroqva’s observation, the older rule of baptism is described in the text, when the catechumens were baptised by dipping in the river [2, p. 351]. As Bidzina Choloqashvili remarked, the author does not mention baptism and it confirms that baptism took place before the 4th century [11, p. 31]. I add that dipping of the children in the water by the priest and saying only the above-mentioned words: “In the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost!” also no mention of chrismatory, dressing in white robes of the children confirm that the above-cited rite of baptism was in accordance with Christian church service of the 2nd century. It is difficult to determine whether the priest creates his own, improvised hymn there, during baptism, or bases himself on the existing hymn in the church service of that time or the hymn that is translated from any language, but one is clear: In the case of translation the translator would have taken account of the existing versification and the nature of musical tradition of that time. The text ends with “Alleluia”, so in my view the hymn might have been musical. It was sung or intoned by cantillation.

I think “zhamoba” that is intoned by the priest during baptism is also significant. “Zhamoba” in old Georgian means “singing a hymn”. According to the text of “The Life of Giorgi Mtatsmindeli” by Giorgi the priest, Giorgi the Hagiorite introduced his pupils’ choir to the emperor in Constantinopole. That time “the king ordered him to sing his orphans zhamoba (hymn)” (Italic mine). After listening to the hymn the emperor thanked the monk and said: “You have taught them in the Greek model, kind monk” and ordered to give them 1000 ajura.”

The text of the hymn that was intoned by the priest was presumably a model of an improvised hymn. It is difficult to determine whether the above-mentioned hymn was the product of the priest’s creativity or one of the components of the liturgy existing at that time. It is not excluded that the hymn had been translated from some other language. From the church history it is well known that the “existence of folk-national musical stream in addition to the professional-canonical hymns wasn’t forbidden and denounced by the holy fathers”[12, p. 129]. The fact is that the above-mentioned hymn was not intoned at baptism after the 4th century.

According to canon 59 of the Laodicean church council “Saying rural psalms is not proper nor of non-canonical books, but canonical ones of the Old and New Testament” [6, p.259] (Italic mine-I.G.).

Therefore, before the Laodicean council singing of folk psalms took place in the church.

Improvised hymns are characteristic of the church service of the 2nd century. As the apostle Paul says only “singing the praise with spiritual mercy” adorns God. Praise, joy and hymn is His much praised (cf. Ps. 32,3; 103,33-34; 104,2).

In the church service the word of praise naturally develops into a hymn. (As we know the reading of the text by the priest, deacon and psalm-reader is intoned by cantillation), but the delighted praise of God is strengthened with music in the words of the hymn (cf. Ps. 80, 2; 88,15, 94, 1; 97,4; Ephes. 5,19). In the heart of the believer who is delighted with God’s majesty, Apostle Paul’s epistle “To the Ephesians” indicates the indivisibility of the word and the music: “Speaking to one another in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing and making melody in your heart to the Lord” (Ephes. 5,19).[1, p.19]. In “The Nine Martyred Children of Kola” the priest praises God with a hymn that comes from the heart during baptism.

Ivane Javakhishvili considered that Georgian church hymn must have been the keeper of the tradition of the same Hebrew hymn and tunes that were spread in the west –in Greece and in the south, in Palestine and Armenia. Contacts with Hebrew, Syrian, Armenian hymns must have ceased from the beginning of the 7th century when unity between the Georgian and Armenian churches was broken. In the collection of hymns by Mikael Modrekili it is noted that he had collected “dzlispirni”, hirmi that he found in the Georgian language “Mekhurni, Greek and Georgian”. The Caesar thanked Giorgi the Hagiorite who brought orphans to Constantinopole after listening to the orphans’ hymn because he had taught them in decent Greek. The scholar notes that the Caesar knew the difference between Greek and Georgian church music well, the modes of Georgian hymn and Greek hymn were different.

Ivane Javakhishvili justly considered that the struggle with pagan tunes must have taken place in Georgia, which is confirmed by evidence in old sources. Namely, in the Syriac text of “The Life of Peter the Georgian” it is said that while many nobles have the habit of listening to songs men and women’s songs, “king Archil instead, like king David, took hymn singers who sang the holy words of God while they were dining and at other time, so that his palace didn’t differ in anything from the church.”

It is seen from the above evidence that fight against pagan Georgian music had already started in the 5th century and king Archil had turned it out of the palace. But of course one cannot infer the final triumph of Christian hymn singing over secular songs on the basis of a single case. Certainly it must have taken a long struggle, especially among people where singing was closely connected with the whole mode of life and activity. In the mountainous region of Georgia the tradition of the declamation of doxologies has survived to the present time. Pagan and Christian cultures blended there and assumed a peculiar image. For example, “The sun has all the features of a deity. In the texts of doxologies of pagan deities the announcement of the sun follows after the Supreme Being”. “Glory to God, thanks to God, Glory to the sun and its follower angels”[9, p.28].

The opinion has been expressed that the syllables and stresses of hymns (doxologies), prayers, kurtkhevani (canonarium, priest’s prayer books) have the same structure as mtibluri (haymaking song), preaching, khmit natirlebi (keening), khutsobani (clerical texts) and are arranged in nine syllable measure. However, an opposite point of view has been put forth, namely that khutsobani are more rhythmic texts.

As is known “In Georgian Hymnography the following widespread forms of hymns are on record: 1. The so-called prosaic hymn; 2. Strophe hymn; and 3. Iambic”[8, p.84]. The hymn in the text of “The Nine Martyred Children of Kola” is rhythmic. The hymn intoned by the priest may be divided into lines and it will take this form:

“The Holy Ghost descended

As a dove upon the Jordan

When Christ was baptized.

The angels stood by singing hymns

Alleluia, Alleluia”.

The primary source for the author of the hymn is the Gospel, particularly the episode of the baptism of Jesus Christ. The four evangelists tell the mentioned fact the same way. The author bases himself on the Gospel according to Mark: “It came to pass in those days that Jesus came from Nazareth of Galilee, and was baptized by John in the Jordan. And immediately, coming up from the water, He saw the heavens parting and the spirit descending upon Him like a dove” (Mark 1, 9-10).

Apolon Silagadze paid attention to the oldest tradition of the inclusion of a poem in a prosaic text. According to him, Pavle Ingoroqva noted that we meet twenty-syllable pistikauri in the Georgian translation of Eusebius’ work “Martyrdom of St. Procopius”: “It is not good to have many masters; have one lord and one king” [3, p.52]. The line is a translation of Homer’s quotation from the “Iliad” [4, p. 113]. The Georgian translation is made from Greek not later than the 7th century [4, p.109], a priori 6th century also [3, p. 52; 10, p. 73].

Such an example of a single verse line occurs have elsewhere too e.g. in the work “On Mystic Theology” by Dionysius the Areopagite, that was translated by Ephrem Mtsire [10, p. 71-73]. Here is a 16 syllable low shairi. Ephrem Mtsire also used twenty-syllable pistikauri to translate Homer in “Ventriloquism of Hellene”: “They heard of /staying of the horse/ on the boose” [3, p. 52].

According to Apolon Silagadze poetry existed with labeled versification system and ecclesiastic poetry was antithesized with it, though the latter gives a fragment of the versification of secular poetry in translating of Homer and one rhythmic twenty-syllable line is fragment of non-ecclesiastic literature.

According to the scholar, the reader of the 6th-7th century sees the same, different 20 syllable structure of the poem as the modern reader. “The author or the translator of ecclesiastic literature used what was established as the rhythmic nature of poetry, the system for ecclesiastic literature wasn’t canonized, wasn’t accepted in literary circles-in the centres of ecclesiastic activity and it has not come down to us in full form. Here poetry, by Byzantine model, was unrhythmic, or later was in Iambic form, like Byzantine”[7, p. 281].

According to the text of Jacob’s zhamistsirva (church service) the priest must focus attention on the baptism of Jesus several times. The priest addresses God with gratitude, because He taught man, as a graceful father and sent His son, because he wanted to renew and to freshen “The image that descended from the Heaven and was embodied by the Holy Spirit and the Virgin Mary and eternal-maiden: Who was born in Bethlehem, in Judea and was baptized by John: and walked among men and all made to live our relatives and as he thought with obedience and of His own accord he decided to die for us the sinful: At night when he was betrayed for the life of the world and he took the bread in His pure and innocent hands…” [14, p. 27] (Italic mine - I.G.). It is noteworthy that in the text of zhamistsirva of the Apostle Jacob the episode of baptism is followed by noting the fact that Jesus was betrayed at night. The opinion is expressed that the author of “The Nine Martyred Children of Kola” notes that the children were baptized at night as Jesus, to absolve the action of the priest why he is baptizing at night. a) It is presumable that the author remembers under the influence of the text of Jacob’s zhamistsirva that Jesus was baptized at night, though if we accept this assumption we have to suppose that this text of zhamistsirva existed in the Georgian language in the 2nd -3rd centuries; b) The author wants to compare the baptism of the children to Jesus’ baptism and to outline the holy significance of baptism. The author describes a true, real story that baptism of the children happened at night, though he notes that the priest did so because he was afraid of the pagans. Though, according to his story, the action of the priest and baptism of the children makes the fact of baptizing as magnific fact in front of the readers and listeners of “The Martyrdom”.

The context of baptizing has a profound theological meaning. By dipping in the water the catechumen divests himself of the old man and will robe a new man. Through his communion with Christ is given grace and ability to strive for the establishment of paradise.

The story described in “The Nine Martyred Children of Kola” took place in the 2nd century which is confirmed by the fact that catechumens were not allowed to enter the church, they listened the hymn outside. It’s known that from the 3rd century a porch was annexed to the church for the catechumens to stand. The church in Kola must have had the form of a cell, approximately of the kind as the oldest building of Nekresi church had. It didn’t have a porch.

The episode of the baptism of “The Nine Martyred Children of Kola” helps us form an idea of the divine service practice in Georgia in 2nd-3rd centuries. It is safe to say that the hymn intoned by the priest is the oldest model of Georgian hymn and researching it in the future will play an important role in the study not only of questions of old Georgian literature, but the history of Georgian church hymn, history of Christian church service and theology in general.

References:

1. Dolidze Dali, Dogma and Tradition in Canonic Church Canticle: coll. “Georgian Church Canticle Nation and Tradition”, Patriarchate of Georgia, Ivane Javakhishvili Institute of History and Ethnology, International Christian Research Centre, Tbilisi 2001

2. Ingoroqva Pavle, Collected Works, Volume IV, Tbilisi 1978

3. Ingoroqva Pavle, Literary Heritage of Rustaveli’s Epoch: The Collection on Rustaveli 750, Tbilisi 1938

4. Kekelidze Korneli, Monuments of Georgian Hagiography, The First Part, Kimeni, II, Tbilisi 1946

5. Ivane Javakhishvili, The Main Questions of the History of Georgian Music, Tbilisi 1990

6. The Nomokanon, prepared for edition by E. Gabidzashvili, M. Dolaqidze, G. Ninua, Tbilisi 1975

7. Silagadze Apolon, "On the initial stages of the development of the Georgian verse": anniversary collection “Akaki Shanidze-100”, Tbilisi 1987

8. Sulava Nestan, Georgian Hymnography, Tradition and poetics, Tbilisi 2006

9. Georgian Folk Poetry, Volume I, Mythological poems, Part I, Tbilisi 1972

10. Qaukhchishvili Simon, "Ephrem Mtsire and the Questions of Greek-Byzantine Versification": Proceedings of Tbilisi State University, XXVII b, 1946

11. Choloqashvili Bidzina, The Oldest Georgian Martyrological Work, Tbilisi 2003

12. Chkheidze Tamar, Georgian Ecclesiastic Hymn in the struggle of General-Christian and National Culture: see coll. “Georgian Church Hymn, Nation and Tradition”, Patriarchate of Georgia, Ivane Javakhishvili Institute of History and Ethnology, International Christian Research Centre, Tbilisi 2001

13. Monuments of Old Georgian Hagiographic Literature, The Book I, prepared by Il. Abuladze, N.Atanelishvili, N. Goguadze, L. Kajaia, Ts. Kurtsikidze, Ts. Chankievi and Ts. Jghamaia, edited by Ilia Abuladze, Tbilisi 1963

14. Old Georgian Zhamistsirva, Georgian text, edited by the committee of the Church Museum, editor: K. Kekelidze, Tiflis, 1912

15. G. I. Shimanski, Mystery and Rites, Liturgy, Edited by the Monastery of Sreten, Moscow, 2003.

|

In this country church service - derived from Jerusalem church service practice - was approved in an early period of spreading of Christianity. In “The Nine Martyred Children of Kola” by an unknown author the character of the service of the apostolic church of the 2nd-3rd centuries is clearly defined. The oldest rule of baptism and the oldest Georgian hymn are reflected in “The Martyrdom”.

In this country church service - derived from Jerusalem church service practice - was approved in an early period of spreading of Christianity. In “The Nine Martyred Children of Kola” by an unknown author the character of the service of the apostolic church of the 2nd-3rd centuries is clearly defined. The oldest rule of baptism and the oldest Georgian hymn are reflected in “The Martyrdom”.