|

The Kartvelologist The Kartvelologist” is a bilingual (Georgian and English) peer-reviewed, academic journal, covering all spheres of Kartvelological scholarship. Along with introducing scholarly novelties in Georgian Studies, it aims at popularization of essays of Georgian researchers on the international level and diffusion of foreign Kartvelological scholarship in Georgian scholarly circles. “The Kartvelologist” issues both in printed and electronic form. In 1993-2009 it came out only in printed form (#1-15). The publisher is the “Centre for Kartvelian Studies” (TSU), financially supported by the “Fund of the Kartvelological School”. In 2011-2013 the journal is financed by Shota Rustaveli National Science Foundation. |

Speech of Alaverdi-Khan Undiladze at the Court of Shah Abbas I

The present publication is an overview of Alaverdi-Khan Undiladze’s speech at the royal court of Shah-Abbas I, proposing the resumption of the Persian-Turkish war, delivered by him at the ending of 1599. This important historical source comes for the first time in the area of research of Georgian orientalists. It is preserved in the book of the English diplomat Antony Sherley on his travel to Persia (Sir Antony Sherley, His Relation of His Travels into Persia, London 1613). The Georgian translation is being published along with the original. keywords:Alaverdi-Khan Undiladze, Shah-Abbas I, Antony Sherley Category: GEORGIAN LITERATURE IN ENGLISH TRANSLATION Authors: ELGUJA KHINTIBIDZE Towards the Ethnocultural Genesis of the Population of the 4th-1st Millennium in the Central Part of the South Caucasus

In the central part of the South Caucasus the boundaries spread of archeaological cultures from the 3rd millenium BC is traditional and they almost precisely fit in new moder limits of Eastern Georgia. This phenomenon should be taken into in the research in the ethnoculteral issues of the local population. The Caucasus is an is isthmus linking Europe and Asia and lying between two seas. Here, over the millennia, based on diverse natural conditions and attending numerous peculiarities, three cultures took shape, with differing material culture and social-economic systems: one in the North and two in the South Caucasus – in its western and central parts. It should be noted specially that notwithstanding the cataclysm so often them caused by external strong influences, marked by many innovations over the epochs, the Caucasian cultures, throughout their existence, continued the main line of their internal development and firmly preserved the stable character and boundaries of diffusion of their inimitable individuality. keywords:Kura-Araxes culture, Bedeni culture, Trialeti culture, Central Caucasian culture Category: SCHOLARLY STUDIES Authors: KONSTANTINE (KIAZO) PITSKHELAURI Towards the Designation of the Amazons [Etymological study]

keywords:Amazons, Greek-Bizantine Sources, Kartvelian tribes Category: SCHOLARLY STUDIES Authors: INGA SANIKIDZE Georgian Verse: Path of Development, Nature, Researchers (A Brief Survey)

Genesis of Georgian verse goes back to pre-Christian times. In Old Georgian written monuments fixed rhyme and metre have been revealed much earlier than in Indo-European verse.The history of Georgian verse knows four reformers: Shota Rustaveli, David Guramishvili, Nikoloz Baratashvili and Galaktion Tabidze. Georgian verse adopted Oriental and European stable verse forms (iambus, mukhambazi, sonnet, etc.), though its main metre is still established: shairi (4444, 5353//3535), shavteluri (55/55), Besikuri (5/4/5), etc. The first Georgian treatise on versification written by Mamuka Baratashvili Chashniki anu leksis stsavlis tsigni (1731) preserves even now not only historical but theoretical value during determination of the nature of Georgian verse. The first half of the 20th century marks the beginning of a new stage in Georgian versification with Sergi Gorgadze’s „Georgian Verse“ (1930), the second half of the 20th century — Akaki Gatserelia’s „Georgian Classical Verse“ (1953) and the beginning of the 21st century — Akaki Khintibidze’s monograph „The History and Theory of Georgian Verse“ (2009). On the path to scholarly research into Georgian verse the most important question still remains the establishment of the nature of national versification: due to the peculiarity of phonological system of Georgian language, it is neither syllabic nor syllabo-tonic, and that is why it is hard to place it in some known systems of versification. keywords: Category: SCHOLARLY STUDIES Authors: Tamar Barbakadze

Georgian Verse: Path of Development, Nature, Researchers (A Brief Survey)

Genesis of Georgian verse goes back to pre-Christian times. In Old Georgian written monuments fixed rhyme and metre have been revealed much earlier than in Indo-European verse. The history of Georgian verse knows four reformers: Shota Rustaveli, David Guramishvili, Nikoloz Baratashvili and Galaktion Tabidze. Georgian verse adopted Oriental and European stable verse forms (iambus, mukhambazi, sonnet, etc.), though its main metre is still established: shairi (4444, 5353//3535), shavteluri (55/55), Besikuri (5/4/5), etc. keywords:rhyme, metre, syllabic, syllabo-tonic Category: SCHOLARLY STUDIES Authors: Tamar Barbakadze Questions about the Origin of the Translation of the Georgian Bible

Georgian Christian culture – literary culture, literary language, conceptual system, literary form, etc. originate from the translation of the Bible. Hence, knowledge of from which language, where, in what circle and when was the Bible translated into Georgian will by itself allow us to shed light on many general and concrete questions in the sphere of religion, culture, history of language and philology. Study of the Georgian Bible from the philological viewpoint obviously begins with the origin of the translation. Otherwise, it is absolutely impossible to determine the text of the Bible, research into the history of the text, discussion of the character of the translation(s) and exegetic or any other type of commentary.

keywords:Georgian Christian culture, he Origin of the Translation of the Georgian Bible, Category: SCHOLARLY STUDIES Authors: ANA KHARANAULI |

Categories Journal Archive |

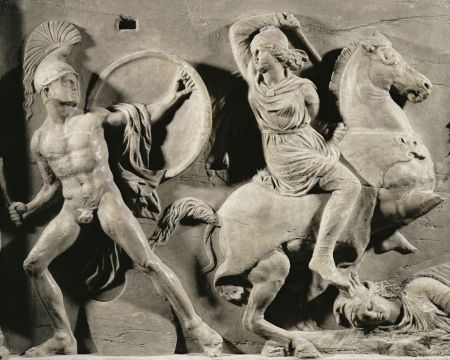

I think that a trace of the Georgian language is seen in the “amazon” stem which supported by several arguments worth mentioning; in particular, Appian’s evidence on “warrior women being called Amazons by local barbarians”, which indicates the non-Greek origin of this name. Simultaneously, in the nominal stem we have to distinguish the Chan –on affix which diachronically had the functions of expressing possessing and multiplicity of similar subjects. According to Herodotus, the Scythian designation “Oiorpata” of the Amazons appears to be a word of complex composition and it is translated into Greek as “people killers”, of these “oior” meant a “man” (//brave) and “pata” “killing, to kill” [Herodotus]. In my opinion, the first segment of the Scythian complex stem must be calque which may have appeared in the Scythian language through the influence of the Georgian languages.

I think that a trace of the Georgian language is seen in the “amazon” stem which supported by several arguments worth mentioning; in particular, Appian’s evidence on “warrior women being called Amazons by local barbarians”, which indicates the non-Greek origin of this name. Simultaneously, in the nominal stem we have to distinguish the Chan –on affix which diachronically had the functions of expressing possessing and multiplicity of similar subjects. According to Herodotus, the Scythian designation “Oiorpata” of the Amazons appears to be a word of complex composition and it is translated into Greek as “people killers”, of these “oior” meant a “man” (//brave) and “pata” “killing, to kill” [Herodotus]. In my opinion, the first segment of the Scythian complex stem must be calque which may have appeared in the Scythian language through the influence of the Georgian languages.