|

The Kartvelologist The Kartvelologist” is a bilingual (Georgian and English) peer-reviewed, academic journal, covering all spheres of Kartvelological scholarship. Along with introducing scholarly novelties in Georgian Studies, it aims at popularization of essays of Georgian researchers on the international level and diffusion of foreign Kartvelological scholarship in Georgian scholarly circles. “The Kartvelologist” issues both in printed and electronic form. In 1993-2009 it came out only in printed form (#1-15). The publisher is the “Centre for Kartvelian Studies” (TSU), financially supported by the “Fund of the Kartvelological School”. In 2011-2013 the journal is financed by Shota Rustaveli National Science Foundation. |

Anthony Anderson

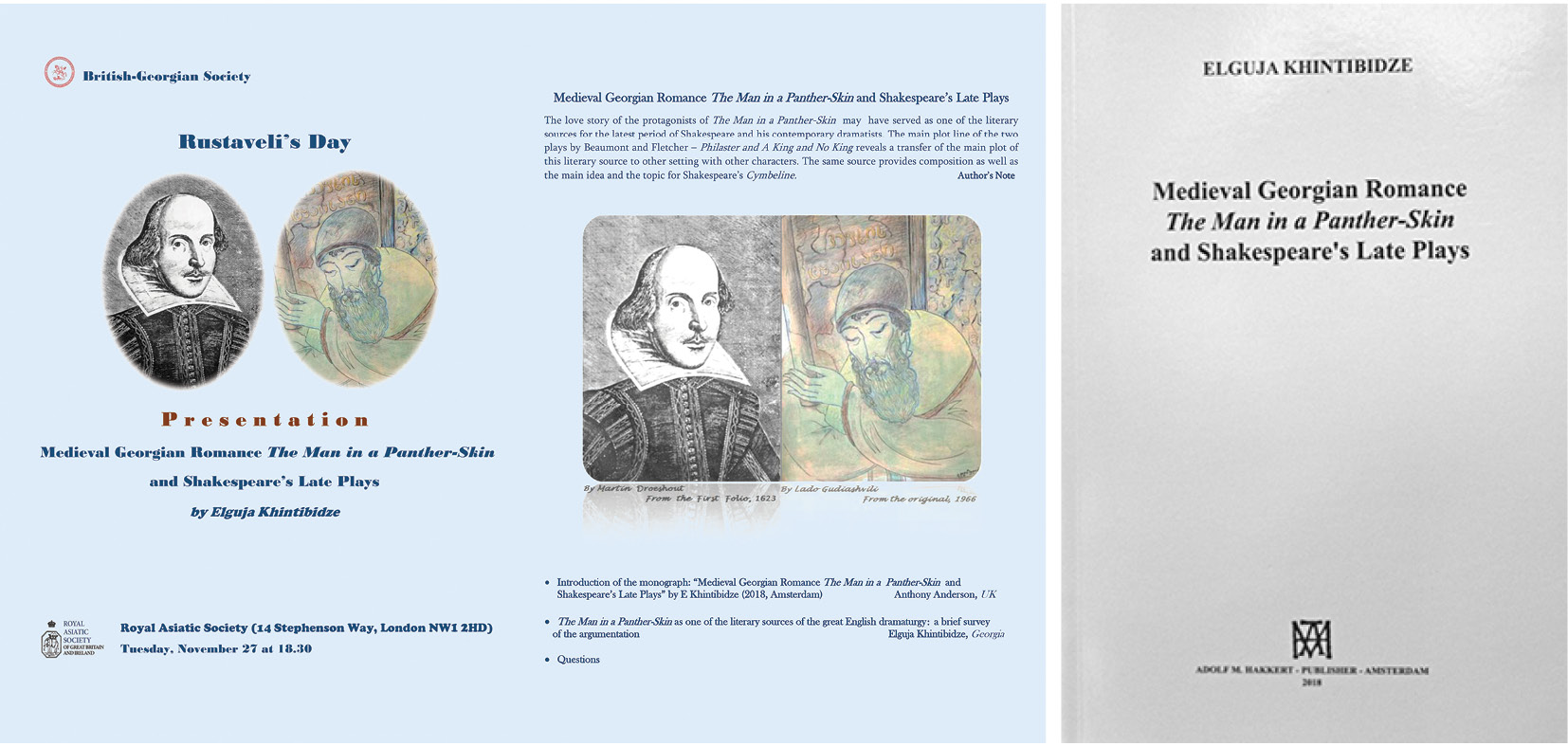

On the Monograph “Medieval Georgian Romance The Man in a Panther-Skin and Shakespeare’s Late Plays” by Elguja Khintibidze

Professor Elguja Khintibidze’s extraordinary studies establish, for the first time, a fascinating connection between English Elizabethan theatre and the great Georgian national 12th century epic by Shota Rustaveli, The Knight in the Panther Skin. Based on the most rigorous textual analysis, he demonstrates, seemingly incontrovertibly, that remarkable similarities in theme, setting, plot, action and character – way beyond any mere coincidence of archetypes – show the clear influence of the Georgian epic upon both Shakespeare and Beaumont&Fletcher, particularly in Cymbeline, and Philaster and A King No King with the last actually set in Iberia, the classical name for Georgia. The most intriguing question is: how did this happen? The staggering explosion of interest in, and information about, the outside world and the equally astonishing enlargement of the English imagination during the Elizabethan era is plain to see in much of the great literature of the time, from Tamburlaine and the Jew of Malta to Othello and The Merchant of Venice. In fact, in Tamburlaine we find one of the earliest reference to Georgia in English, rather than to Iberia or Colchis, names long familiar through the classics. Even earlier, in 1356, John Mandeville writes about Georgia in his Travels, and there are intriguing possibilities of connections between English and Georgians, certainly of an English consciousness of Georgia, through the Crusades, Constantinople, monks, soldiers and diplomats even before this. But it is really in the Elizabethan age – with the fantastic explorations of the great sailors, travellers and merchants – that the wide world floods in. The voyages of Anthony Jenkinson and The Muscovy Company (1558-1571), of Anthony Shirley and his adventures in Persia (1599), brought Georgia much nearer to home. Both their accounts fed into the literature of the day and the huge and growing appetite for the exotic. The setting for many books and plays of the time were based upon well-known literary texts, popular tales, travels and histories. All this provided just the right environment for Professor Khintibidze’s brilliant account. His establishing of the probable link that draws Shakespeare and Rustaveli together is a wonderful piece of research, both enthralling and surprising: most probably not through Muscovy or Persia as one would have expected but through Spain, England’s arch-enemies at the time. Georgian embassies arrived there in 1495 and 1598, bearing lavish gifts and, of course, all their culture and learning. A great deal of correspondence flowed between the two courts in the intervening years. Fletcher, we know, spoke Spanish and there are interesting indications of considerable cultural exchange, largely through monks and priests, between England and Spain, particularly before the Reformation but also after. He, particularly, seems to have lifted his plot entirely from Rustaveli. Shakespeare, of course, pillaged everything he could get his hands on and was close to Beaumont & Fletcher. All this is wonderfully teased out, explained and elucidated in Professor Khintibidze’s seminal book, certainly one of the most important and interesting contributions to have come out of the academic world of Georgian-English studies in many years. It is a tremendous example of the astonishing inter-connectedness of cultures, of stories, of interests, many centuries before such things were available at the click of a button, and a marvellous tribute to the power and the poetry of Shota Rustaveli’s fabulous epic.

|

Categories Journal Archive |