|

The Kartvelologist The Kartvelologist” is a bilingual (Georgian and English) peer-reviewed, academic journal, covering all spheres of Kartvelological scholarship. Along with introducing scholarly novelties in Georgian Studies, it aims at popularization of essays of Georgian researchers on the international level and diffusion of foreign Kartvelological scholarship in Georgian scholarly circles. “The Kartvelologist” issues both in printed and electronic form. In 1993-2009 it came out only in printed form (#1-15). The publisher is the “Centre for Kartvelian Studies” (TSU), financially supported by the “Fund of the Kartvelological School”. In 2011-2013 the journal is financed by Shota Rustaveli National Science Foundation. |

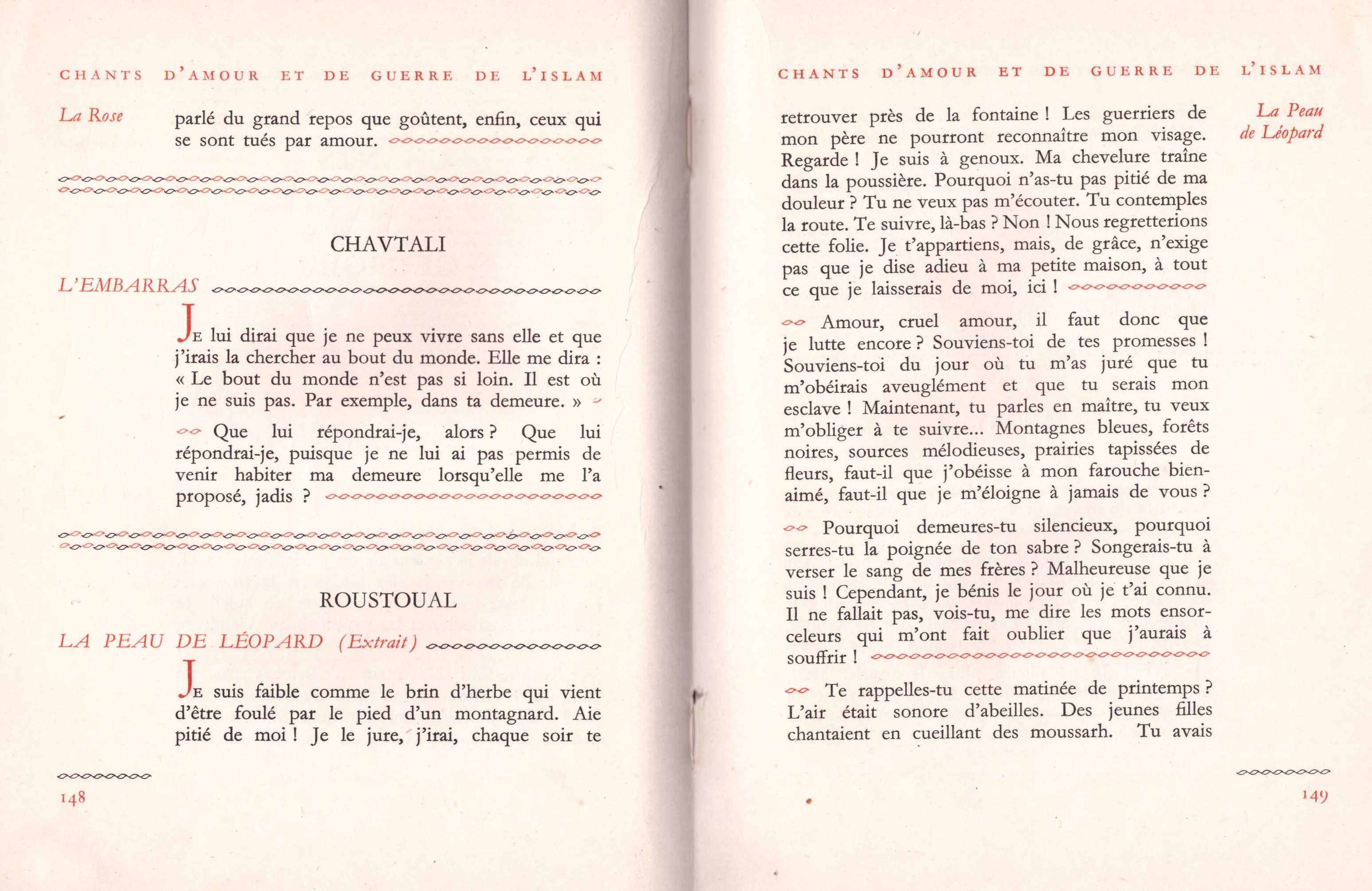

The Mystery of the Unknown Poem by Rustaveli The present issue of the Journal introduces a French translation of the unknown poem considered to be written by Rustaveli along with Georgian translation performed from that French original. The French translation of the poem caused a lot of controvery among Georgian scholarly circles and mass media in the 20th century. A compilation of poems translated from Arabic into French titled as “The Islamic Songs of War and Love” was published in 1942 in Marseille. The translator as well as the editor of the book was Franz Toussaint. The compilation includes prosaic translations of Arabic, Persian, Afghan, Belujistan, Altarian, Turkish, Egyptian, Maroconian, Hogarian, Cherqezian and Georgian poems with the following subtitle – “Géorgie” The Georgian part of the book includes four poems: Prince Zoumali La Rose, Chavtali L’ Embarras, Roustoual La Peau de Léopard, Anonime Nuit. However, the poems have not been identified by Georgian sources and only Rustaveli and Shavteli are considered to be the authors of the poems, whose names are suggested in an altered transliteration by a French compilation – Roustoual, Chavtali. Georgian media learned about the compilation only in the middle of the previous century and the controversy over the facts concerning the genuinity of the publication is still going on. The authorship of Rustaveli is one of the major issues of the discussions. Some commentators fully deny the genuinity of the facts provided by Franz Toussaint since the poems have not been verified by Georgian sources and some parts of the reports are obscure. The name of the Rustaveli poem The Tiger Skin fails to reveal any links with The Knight in a Panther Skin by Rustaveli. The reason the names of Shavteli and Rustaveli are mentioned is absolutely unclear. Georgia is surrounded by Muslim countries and what is more important, adoption of Rustaveli’s name for other poems in newspaper or journal publications in the 19th-20th Century is not scarce at all (The Anthology by A. Thalasso, translations by Trikoglidis). The opinions of the commentators supporting Franz Toussaint’s publications as to be the most important novelty are based upon the following viewpoints: Franz Toussaint is far from being an armature writer or a journalist, seeking for sensational facts and financial benefits. Rather, he is an outstanding expert of Oriental studies as well as a translator of Arabian, Persian and Sanskrit poetry. His publications are designed for wide variety of people rather than for one or two nations in particular. His compilations include examples of a classical works of Oriental literature such as: Jalal ad-Din Rumi and Hize, Rubiyát of Omar Khayám, extracts from The Thousand and One Night, etc., more importantly the examples of the religious Oriental literature such as verses from Quran. Through oral interpretations Franz Toussaint explained Georgian experts interested in this issue that he was able to obtain the information concerning Rustaveli from a compilation of Arabic poems by Abu'l Faraj from Cairo university bookstore. This author is considered to be from Syria, a Christian Arab writer born in 1225 (some researchers specify his name as Abu'l-Faraj Ibn al-Ibri). This famous Syrian writer, translator and a compilator served as a bishop in Armenia and lived in Azerbaijan. His written records have retained information on Iberians, conversion of Georgian people to Christianity and Georgian-Mongol relationship. All doubts against the authencity of Toussaint’s publications are only allegetions. All of them can also serve as indications to genuine facts. Altered transliteration of the names of Shavteli and Rustaveli (Rustval/Rustual, Shavtal) can be explained either through specificity of Arabic language leading to erroneous pronunciation of the word or repetition of the wrong interpretation of the word given in French encyclopedias. We should assume that the poem by Rustaveli was taken from the manuscript which started by the poem The Man in the Panther Skin and the title of the poem could have arisen from the title of the manuscripts (or the book). In addition, the title The Tiger Skin may also be considered as a translation of the Georgian The Man in the Panther Skin. The title of the poem by Rustaveli was initially translated by both scholars and translators. Therefore, the authenticity of Toussaint’s publication cannot be challenged yet. On the other hand, we should exempt ourselved from thinking that Rustaveli was the author of the peom published in French. The questions call for more insightful examination as some of its facts cannot be ignored. The aim of the present publication is to strengthen the international interest towards the issue. This issue calls for more thorough study of Syrian book-stores as well as large libraries overseas from both groups of experts and armature travelers interested in this issue as Rustaveli is a genuine phenomenon of our civilization and its works should not be left unheeded by the modern epoch. The French text of the book considered to be written by Rustaveli is published from the book by Franz Toussaint, Chants d’amouret de guerre de l’islam, Marceilis, 1942: The first Georgian translation is extracted from the review published in the journal “Saqartvelo”, #1, January, p. 53. The author of the review is B. Vardani. The second Georgian translation is performed by M. Mamulashvili – extracted from the journal “Drosha”, #11, November 1059, Tbilisi, p. 10 (Micheil Mamulashvili, “Unknown Poem by Rustaveli”) The Editor Roustoual La Peau de Léopard (extrait) Je suis faible comme le brin d’herbe qui vient d’être foulé par le pied d’un montagnard. Aie pitié de moi! Je le jure, j’irai, chaque soir te retrouver près de la fontaine! Les guerriers de monpére ne pourront reconnaître mon visage. Regarde! Je suis à genoux. Ma chevelure traîne dans la poussière. Pourquoi n’as-tu pas pitié de ma douleur? Tu ne veux pas m’écouter. Tu contemples la route. Te suivre, là-bas? Non! Nous regretterions cette folie. Je t’appartiens, mais, de grâce, n’exige pas que je dise adieu à ma petite maison, à tout ce que je laisserais de moi, ici! Amour, cruel amour, il faut donc que je lutte encore? Souviens-toi de tes promesses! Souviens-toi du jour où tu m’as juré que tu m’obéirais aveuglément et que tuserais mon esclave! Maintenant, tuparlesen maître, tuveuxm’obliger à te suivre… Montagnes bleues, forétsnoires, sources mélodieuses, prairies tapissées de fleurs, fraut-il que j’obéisse à mon farouche bien-aimé, faut-il que je m’éloigne à jamais de vous? Pourquoi demeures-tu silencieux, pourquoi serres-tu la poignée de ton sabre? Songerais-tu à verser le sang de mes frères? Malheureuse que jesuis! Cependant, je bénis le jour où je t’aiconnu. Il ne fallait pas, vois-tu, me dire les mots ensorceleurs qui m’ont fait oublier que j’aurais à souffrir! Te rappelles-tu cette matinée de printemps? L’air était sonore d’abeilles. Des jeunes filles chantaient en cueillant des moussarh. Tuavaisgardé ma main dans la tienne. Tu regardais une hirondelle dont le vol traçait dans le ciel les mots d’un hymne à la lumière et à la joie. Il est loin, ce jour! Que de larmes j’ai versées, depuis! Mais, tu pleures, tu pleures… Pose ton front sur mon épaule et laisse couler tes larmes. Ecoute le murmure du ruisseau. Il te remercie d’avoir renoncé à ton project terrible. Ecoute le murmure de la forêt. Elle te dit qu’elle nous offrira toujours ses mousses. CHANTS D’AMOUR ET DE GUERRE DE L’ISLAM FRANZ TOUSSAINT 19A, RUE VENTURE, MARSEILLE – 1942

რუსთუალ ტყავი ვეფხისა (ნაწყვეტები) ვარ სუსტი, ვით ყლორტი ბალახისა, რომელიც ეხლახან გასთელა მთიულის ფეხმა. შემიბრალე მე! გფიცავ, ყოველ საღამოს მოვალ, გიხილო შადრევანთან! მამაჩემის მხედრები ვეღარ სცნობენ ჩემს სახეს. შემომხედე! დაჩოქილი ვარ. ჩემი კულულები ჩაცვენილია მტვერში. რატომ არ შეიწყალებ ჩემს მწუხარებას! შენ არა გსურს მომისმინო. შენ დასჩერებიხარ გზას. გამოგყვე შენ, იქით? არა! ჩვენ ვინანებთ ამ სიგიჟეს. მე გეკუთვნი შენ, მაგრამ ჰყავ წყალობა, ნუ მომთხოვ, ვუთხრა „მშვიდობით“ ჩემს პაწია სახლს, ყველაფერს მას, რასაც ჩემგან მე აქ დავტოვებდი! სიყვარულო, სასტიკო სიყვარულო, განა მე კვლავ უნდა ვიბრძოლო? გახსოვს შენ დაპირებანი შენნი! გახსოვს ის დღე, ოდეს შემომფიცე, რომ ბრმად დამემორჩილებოდი და იქნებოდი მონა ჩემი! ეხლა, შენ ბრძანებ უფალივით, შენ გსურს, მაიძულო გამოგყვე შენ... მთანო ლურჯნო. ტყენო შავნო, წყარონო ხმატკბილნო, ველნო ყვავილებით მოფარდაგებულნო, განა უნდა დავემორჩილო ჩემს მრისხანე სატრფოს, განა უნდა სამუდამოდ მოგცილდეთ თქვენ? რატომ ბრძანდები ჩუმად? რატომ უჭერ ხელს შენი ხრმლის ხეტარს? ჰფიქრობ დაანთხიო სისხლი ძმათა ჩემთა? ვაი მე ბედშავს! მაინც ვლოცავ იმ დღეს, როცა მე შენ გაგეცან. ხედავ, არ უნდა გეთქვა ჩემთვის სიტყვანი მომჯადოებელნი, რომელთაც დამავიწყებინეს, რომ მე სატანჯველს მივეცემოდი. გახსოვს, შენ ეს დილა გაზაფხულისა? ჰაერში იყო ხმოანება ფუტკართა. ასულნი გალობდნენ მუსარის კრეფის დროს, ჩემი ხელი ხელთ გეჭირა. შენ უცქეროდი მერცხალს, რომლის კამარამ გამოჰკვეთა ჰაერში სიტყვები დიდებისა, სინათლისა და სიხარულისადმი. შორსაა ეს დღე! რაოდენ დავღვარე მე ცრემლნი მას შემდეგ! მაგრამ შენ სტირი, სტირი.... დაასვენე შუბლი შენი ჩემს მკერდს და დეე იდინოს შენმა ცრემლებმა. ყური დაუგდე წყაროს ჩურჩულს. იგი შენ გითვლის მადლობას, ვინაიდან შენ უარჰყავ სასტიკი გეგმა შენი. მოისმინე ჩურჩული ტყისა. იგი გეუბნება შენ, რომ შემოგვთავაზებს მუდამ თავის ლბილ ხავსს.

რუსთაველის უცნობი ლექსი სუსტი ვარ, ვითარცა ყლორტი ბალახისა, რომელიც ეს-ეს არის გათელა მთიელის ფეხმა: შემიბრალე მე! გფიცავ, ყოველ საღამოს მოვალ, გიხილო შადრევანთან. მამაჩემის მხედრები ვეღარ ცნობენ ჩემს სახეს. შემომხედე! დაჩოქილი ვარ. ჩემი კულულები მტვერშია ჩაცვენილი. რატომ არ თანაუგრძნობ ჩემს მწუხარებას? შენ არა გსურს მომისმინო. შენ დასჩერებიხარ გზას. გამოგყვე იქით? არა! ჩვენ ვინანებთ ამ სიგიჟეს. მე გეკუთვნი შენ, მაგრამ მოიღე მოწყალება: ნუ მომთხოვ, ვუთხრა მშვიდობით ჩემს პაწია სახლს, ყველაფერს, რასაც ჩემგან აქ დავტოვებდი! მიჯნურობავ! განა მე კვლავ უნდა ვიბრძოლო? გახსოვს დაპირებანი შენნი? გახსოვს ის დღე, ოდეს შემომფიცე, რომ ბრმად დამემორჩილებოდი და იქნებოდი მონა ჩემი! ახლა შენ ბრძანებ უფალივით, გსურს მაიძულო გამოგყვე შენ... მთანო ლილისფერნო, უღრანო ტევრნო, წყარონო ხმატკბილნო, მინდორნო ყვავილებით მოფარდაგულნო! განა უნდა დავემორჩილო ჩემს მრისხანე მიჯნურს, განა უნდა სამუდამოდ მოგძულდეთ თქვენ? რატომ ხარ ჩუმად? რატომ უჭერ ხელს შენი ხმლის ვადას? იქნებ ფიქრობ, დაანთხიო სისხლი ძმათა ჩემთა? ვაიმე ბედშავს! მაინც ვლოცავ იმ დღეს, როცა შენ გაგიცან. ხედავ, არ უნდა გეთქვა ჩემთვის სიტყვანი მომჯადოებელნი, რომელთაც დამავიწყებინეს, რომ მე სატანჯველს მივეცემოდი. გახსოვს ის დილა გაზაფხულისა? ჰაერში იდგა ხმოვანება ფუტკართა, ასულნი გალობდნენ მუსარის კრეფის დროს. ჩემი ხელი ხელში გეჭირა. შენ უცქეროდი მერცხალს, რომლის კამარამ აწერა ჰაერში სიტყვები დიდებისა, სინათლისა და სიხარულისა. შორს არის ის დღე! რაოდენი ცრემლი დავღვარე მას შემდეგ, მაგრამ შენ სტირი, სტირი... დაასვენე შუბლი შენი ჩემს მკერდს, დაე, იდინოს ცრემლებმა შენმა. ყური მიუგდე წყაროს ჩურჩულს. იგი შენ გითვლის მადლობას, რამეთუ შენ უარყავ სასტიკი ზრახვანი შენნი. ისმინე ჩურჩული ტყისა, იგი გეუბნება, რომ ნიადაგ შემოგთავაზებს თავის ლბილ ხავსს.“

|

Categories Journal Archive |